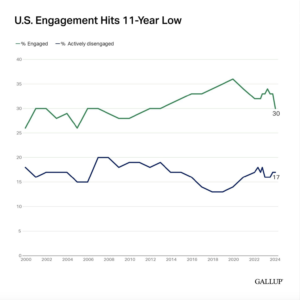

A recent Gallup poll found that employee engagement is at an 11-year low, with one of the reasons for disengagement being a lack of clarity about work-related roles and responsibilities.

Lack of clear communication at work comes from all directions; employees hide mistakes and opinions from the management, colleagues do not share information or ideas with one another, and the management lacks transparency about which considerations are included in decision-making. Given that we know that communication is crucial for the success of a company (Bucata & Rizescu, 2017), and that organizations that fail often site poor communication as a top reason (Rana, 2013), why is it so difficult for employees across all levels to clearly communicate with one another?

What is communication?

Talking and communicating are not the same. Talking entails the use of language to express a thought, an anecdote, an idea, an inquiry, etc. Communication, on the other hand, is the more purposeful act of ensuring that the individuals we interact with are understanding what we mean. That could require us to repeat ourselves, clarify, re-state our point using other words, answer questions, etc.

When we communicate, we need to carefully choose our timing, tone, vocabulary, and body language, in order to get our point across in an optimal way and shape future interactions. For example, a nurse describing to a child patient the process of getting his or her blood drawn will communicate in a much different way than if she was talking to an adult patient. The goal of the nurse is not only to verbalize the procedure of drawing blood; she also aims to make the child comfortable so that he or she will cooperate and make the experience as positive and efficient as possible.

Barriers to communication at work

Cooperation is one of fundamental requirements of a workplace, and it largely depends on communication. While we may believe that communication should be simple and straightforward, it is not without its barriers. One of the biggest obstacles to communication in the workplace, is the illusion that communication has been accomplished (Shaw, 2011). In other words, while talking may take place (such as when a manager talks to an employee in a one-on-one meeting), it is missing the goal of ensuring a thorough understanding of what is being said. The result is that employees are often unclear about their roles and responsibilities, and management comes to perceive employees as being unable to follow orders and complete tasks.

Another barrier to communication includes individuals’ attitudes. One such attitude involves power and status, and it can affect both the transmission and reception of communication (Rani, 2016). For example, if a manager believe that a person in their position should be listened to and obeyed  indisputably, they will order employees around without explanations or clarifications. On the other hand, if employees have a built-in resistance to authority figures, this may limit the extent to which they listen to, and try to understand what is being communicated to them.

indisputably, they will order employees around without explanations or clarifications. On the other hand, if employees have a built-in resistance to authority figures, this may limit the extent to which they listen to, and try to understand what is being communicated to them.

Furthermore, if colleagues believe that the only way to grow within their company is by withholding beneficial information from others (which may be true, when the organizational culture is maladaptive), they will refrain from communicating, even about essential facts and processes.

Finally, too much information was found to be a profound barrier to communication in the workplace (Sapungan et al., 2019). Specifically, when leaders or managers provide too much information to employees, when policies and procedures constantly change, and when there are too many meetings, employees simply have too much material to sort through, which creates an overload and blocks communication.

Therefore, when it comes to communication, more isn’t necessarily better. Too much information, just like too little information, appears to be unfavourable. The challenge with workplace communication is not only to learn to communicate (as opposed to merely talk), but also to find a happy medium where employees have enough information to perform their job with engagement, purpose, and alignment with the organization, yet they are not burdened with more than they have the capacity to process.

About the author

Dr. Anna Sverdlik is the founder of Melioscope. Since 2011, she has been specializing in uncovering organizational structures that shape motivation, engagement, and well-being.